The usual occupation of the Celts was agriculture, livestock, hunting, fishing and gathering nuts, for which settlements have been found in many tools.

Agriculture

The land and crops grown

Poor soil, combined with the altitude and harsh climate, made it difficult to practice intensive agriculture in the territory. In these circumstances, the maintenance of a growing population must be made from extensive use, both for farming and for livestock

The classical texts refer to the deficit of cereal, at least in certain areas, as Appian tells how the merchants sailed up the River Douro area leading to Numancia wine and cereal. The alternative to this lack of livelihood was provided by forests of oak, with acorns contributing to food and feed, as well as other nuts such as walnuts. The analysis of the mills found in Numancia indicate a greater use for processing acorns cereal diet contributing to their high nutritional value and, after milling, flour was obtained with which to bread and porridge, as with the cereal.

Agriculture is practiced mainly rainfed cereal production, with different varieties of wheat and barley resistant to cold weather (it is common to observe very small wheat crop appears tremesino), supplemented with some legumes. There are different types of legumes (vetch, yeros, vetch). In certain suitable areas of the valley of the Ebro and the Duero was practiced horticulture, cultivation of fruit trees (pear quoted numantina) and vine (grape seeds are known in Herrarea of Navarre and a small winery in Segeda) dated from III century BC The lack of wine was replaced by the beer, called Caeli, your favorite beverage, which was made from wheat, which ferment gave a harsh taste and intoxicating heat.

Technology and Landscape

To address this bet agricultural safeguards were necessary to develop appropriate technology, so will the Celts who first made this area a wide range of tools designed to make effective iron farm work, replacing the previous stone wood, and incorporating other appropriate to new work and follow-up of the new way of life.

These tools are well documented in the archaeological Celtiberian, establish the same kind used subsequently rural life until the advent of the tractor, the plow with a metal railing, pulled by oxen, and restobar for cleaning, the hoes and hoes to eliminate competition from other herbs, the sickles to harvest. Then came the haul up the beds or sites suitable for threshing, of which there are constant references in the classical texts, which stirred the pile with forks and forks (sometimes called metal) and winnowed the chaff.

Having cleaned the grain was moved to the village, as living spaces offer clean seed husks and other byproducts of threshing. Then the grain was kept in jars at home and was crushed, like acorns, circular hand mills, called by Pliny hispaniensis molas and some amygdaloidal, of ancient origin.

The introduction of the plow and crop rotation practice would involve the use of fallow, and probably natural Subscriber etched in the landscape well-defined fields, clicking on the moors and forests of oaks, pines and junipers, looking to the river above the narrow strip of orchards (Legon worked with hoes and found in different sites) that, around town, provide in the warm months of spring and summer a significant base for its food needs, as this product cool.

- Agriculture and Society

The extension of agricultural land and the gradual process of settling land would break the mountain ridges and valleys duality of rivers, limiting the weight in the mountain regions, the predominant livestock use. This will involve the construction of a hierarchy of rights over land use, which will favor some and hurt others, you have to relate to the beginning of the gradual dismantling of large structures parents.

This is compounded by the unequal access to means of production would become more complicated, as the techniques were more complex and costly, as the introduction of the plow, which involved the availability of animals for traction and implements appropriate, generating patterns of personal relationship between the owner of the land and the necessary technology and offering their work in exchange for a share of production, establishing new relations of dependency.

Livestock

-Livestock and wealth

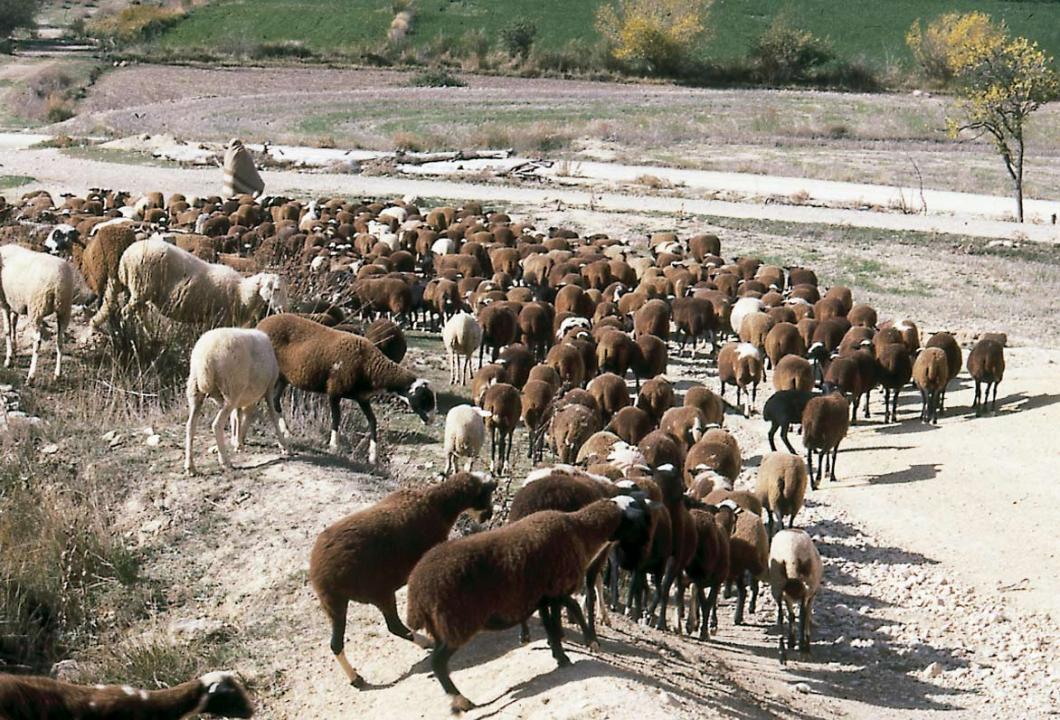

The cattle represented wealth, the most abundant animal in the Celtiberia, around 50%, were the sheep and goats, especially the first (according to Strabo, "the whole Iberia breeding goats and wild horses in abundance ...") , followed by cattle (20%) and a lower percentage of pigs (5 to 10%). Cattle, and served as a pulling force, would also contribute to the provision of milk, cheese and curd, hides and skins, and use their horns to the whetstone holders and spoons and other utensils manufacturing.

Highlighted the sheep industry in addition to being a good complement to agriculture, since it uses the stubble pastures, provides credit to the fields and milk and dairy products for human consumption. To this must be added the use of wool for the manufacture of clothing and skin for leather, and skins botos. Among the highlights clothing "sagum" warm clothes to fend off the harsh climate, which was highly appreciated by the Romans, as is clear that war between the taxes required to always appear Celtiberian cities thousands of these items, in the year 141 BC at Numancia and demanded they Termes 9000.

-Transterminance and wetlands

Livestock through the transterminance (alternation of pastures in the valleys, in winter, with the high mountains in the summer), was complementary to the agricultural productivity deficit. They took advantage of oak and juniper woodlands and wetlands and marshes, which had a wide distribution in the past, because the drainage of water from the rivers was more superficial.

These large lake areas were an important reference point for livestock, as they provided the possibility of maintaining the freshness of the grass in the summer season to avoid travel to high peaks. The economic orientation favorable to agriculture, from the nineteenth century, with the liquidation of the Mesta, led to drying of many of these areas.